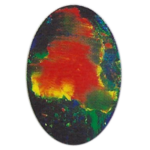

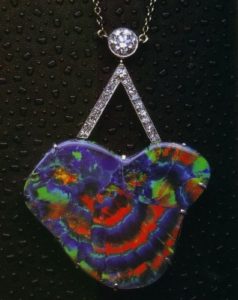

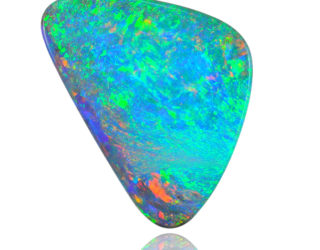

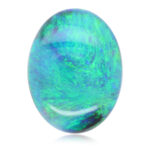

“Aurora Australis” (picture and information courtesy of Altmann & Cherny)

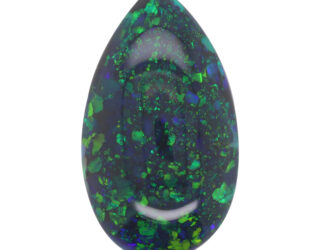

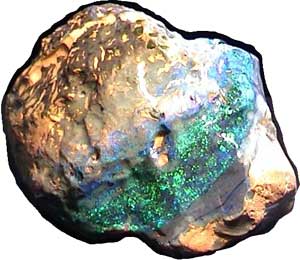

The “Aurora Australis” was found in 1938 at Lightning Ridge and is considered the world’s most valuable black opal. The oval, cut and polished stone has a harlequin pattern with dominant red, green and blue colors against a black background. It weighs 180 cts. and is 3 inches by 1.8 inches. The rarity of the opal comes from its size and strong, vibrant colour play. It weighs 180 carats and its dimensions are 3 inches x 1.8 inches. Dug from an old sea-bed it has the distinctive impression of a star fish on its back. It was valued at AUD$1,000,000 in 2005.

The Aurora is the first large, fine, Australian opal mentioned in literature. Charlie Dunstan had found another large opal previously, but its blue-green colour play was not considered valuable at the time – although the stone weighed about 12 ounces (close to 1860 carats). At a depth of approximately six metres, Charlie found the brilliant gem. This treasure was rumored to have brought Dunstan 100 pounds. Altmann & Cherny purchased the opal in a semi-rough state (a rub). They cut and polished the opal into its oval shape, and realising what a true gem they had, they named it the “Aurora Australis” after the bright southern lights in the night sky.

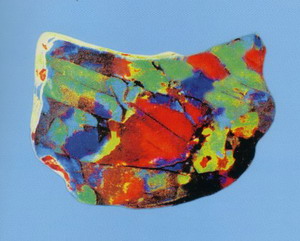

“Fire Queen”

In November 1906, Charlie Dunstan found “Dunstan’s Stone” (Later renamed to “The Fire Queen”), at the Angledool Diggings. She weighed in at about 6.5 oz. or nearly 900 carats. She was the largest nobby to date – alive with colour – “truly a marvelous gem, too beautiful for words!”

After selling the stone for a paltry £100 to an unknown buyer on a trip to Angledool, the story goes that Dunstan got drunk and “lost” two other big stones. In November 1910, Charlie Dunstan was found dead in his hut from a gunshot wound to the head. The verdict was that he had committed suicide.

After being originally sold for a mere £100, the stone changed hands several times, each new buyer finding it difficult to sell as there was hardly any market for big black opals in those days. By 1928, however, it was in the Chicago Museum, valued at £40,000 after being renamed “The Fire Queen”. In the 1940’s, it was then resold to J.D. Rockefeller for £75,000, who donated her to his prestigious family collection.

“The Black Prince”

‘The Black Prince’, originally known as ‘Harlequin Prince’, was found in 1915 at Phone Line by Urwin and Brown. Perhaps the least significant of the four notable stones from the same claim, this gem weighed 181 carats and displayed a flag pattern one side and the other was red. There was a sand hole in the face.

This black opal was acquired in England by a wealthy American serviceman, and later donated to the New York Museum of Natural History. Later ‘Prince’ became part of the collection at Forest Lawn Memorial Cemetery, Los Angeles, and was stolen at the same time as ‘Pride of Australia’. ‘Flamingo’ was the largest of the four notable stones in the Phone Line patch, weighing over a quarter of a pound at 800 carats! This black opal plus ‘Black Prince’, ‘Pride of Australia’ and ‘Empress’ were the ones for which Sherman paid Urwin and Brown £2000 in about 1920. This was the most ever paid to that date for four black opals. Ernie’s sister Bertha named the stones.

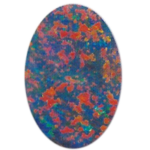

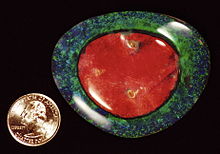

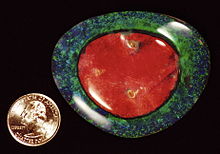

“Pride of Australia / Red Emperor”

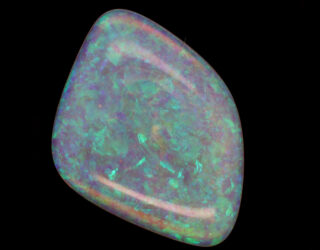

(picture from www.resources.nsw.gov.au)

‘Pride of Australia’, also known as ‘Red Emperor’, was found in 1915 by Tom Urwin and Snowy Brown at Phone Line (off Fred Reece Way). The Pride of Australia is shaped like the continent. The 2″ x 3″ opal has black and blue veins interlaced with brilliant red streaks. By 1954, it had toured at least five World Fairs as “the greatest opal of Australia, and therefore the greatest opal in the world.”

This double-sided gem cut to a 225 carat stone that just fit into a tobacco tin. There were two distinct colour bars. The one on the back was much lighter and almost harlequin, totally different to the main bar of dark, rich flashes of colour. Ernie Sherman bought ‘Pride’ plus another three stones from the miners for £2000 around 1920. It was the highest price ever paid for four black opals. The ‘Pride of Australia’ was valued in 1931 at £2000 on its own, and was sold in the 1950s from the Percy Marks Collection, Sydney.

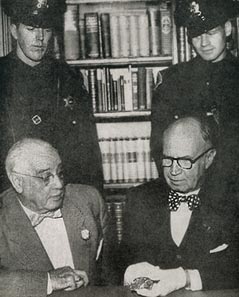

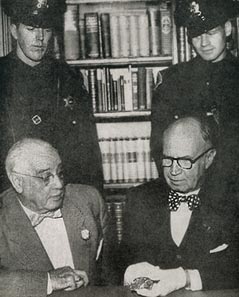

Dr. Eaton examines his “Pride of Australia” opal

with the Collector of Customs while guards look on.

In 1954, Dr. Hubert Eaton was the President and Founder of the world-famous Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, CA, and owner of one of the most important gem collections in the United States. Percy Marks, Ltd., located in Sydney, Australia, was home to the opal when Dr. Eaton was craving for his collection. This firm was supposed to have the greatest opal collection in the world. The Pride of Australia was sitting in the display window when Dr. Eaton arrived.

To Dr. Eaton’s dismay, the opal was not for sale. Dr. Eaton chose several other opals and told the firm that he wanted all of these opals plus the Pride — if the Pride wasn’t thrown in with the deal, then there would be no deal. Dr. Eaton wrote in a letter to his assistant, “Well, to cut a long story short, after quite a time, it ended by my going to the bank and getting a draft payable to Percy Marks, Ltd.”

Some say the price was £150,000, but Greg Sherman reckons not more than £50,000 was paid for this mostly green-shot-with-orange black opal. ‘Pride’ was later stolen from the new owner, Forest Lawn Memorial Cemetery, Los Angeles.

“Empress of Australia”

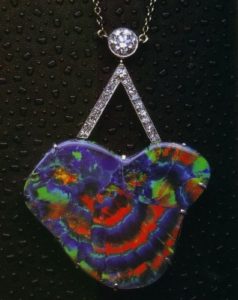

‘Empress of Australia’ was mined in 1915 from the same patch on Phone Line as ‘Pride of Australia’ by Urwin and Brown. First known as ‘Kaleidoscope Queen’, then ‘Tartan Queen’, this stone measured 3 x 2 3/4 x 2 1/4 inches in the rough.

The stone was shaped out and polished to reveal the glowing patches of red to best advantage, probably weighing 500 carats. Later, down at the pub, this, the most colourful black opal from the claim, slipped through the fingers of a local admirer, and fell to the floor, breaking into two pieces. Two almost matching stones were cut out of the first piece, each measuring 2 inches long and weighing 20 carats. Ernie Sherman’s daughter designed a beautiful pendant for one half. The second piece of ‘Empress’, measuring 1 3/4 x 1 1/2 inches and weighing 50-60 carats, was mounted in a gleaming necklet of brilliants.

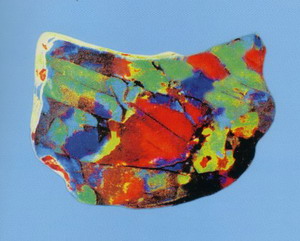

“The Flame Queen”

The ‘Flame Queen’ was mined on Bald Hill in 1918, not far from where Dunstan mined ‘Queen of the Earth’ in 1906. Three partners, Jack Phillips, Walter Bradley and “Irish” Joe Hegarty took over a partially dug claim that was abandoned by a miner who left to fight in World War I.

Lightning Ridge was a risky place to speculate for opals. The early miners used picks and shovels, battling fatigue and hunger and desperate to find an opal-rich shaft. Hegarty completed the partially dug tunnel, but when he reached the opal level, the site appeared worthless.

The opal-rich clay, usually around 30 feet down the shaft, did not reveal any colour, which indicates the presence of gemstones. Once Hegarty reached the clay, he and Bradley tunneled vertically, a dangerous procedure that could result in the collapse of the entire site.

At this level, with little ventilation and light, Bradley discovered a “great nobby”. Close to 35 feet below the surface, in a tunnel little more that 2½ feet wide, he was hoisted up so that he could examine the stone under daylight.

The story goes that Walter Bradley took a “bite” at “a great black nobby” with his steel snips… and revealed the brilliance of opal within. They were offered £7 in the rough for the stone, which they refused. Of the three partners, Bradley was the most skilled lapidarist and had the best equipment to cut and polish the rough. It revealed a dazzling red domed center with a greenish blue border. The three men, broke and exhausted from their labor, hungry from scarce food supplies, hastily sold the opal to a gem buyer for 93 pounds.

Phillips, Bradley & Hegarty were the lucky miners, who shared the £93 that Ernie Sherman gave them for this collector’s piece. Cutting it would have spoilt the unique pattern. John Landers reported that the architecture “made this stone!” A black nobby as big as the palm of a hand, ‘Flame’ weighed 253 carats. An oval, 2 3/4 inches x 2 1/3 inches, with a dome that a half-crown would not cover, displayed a broad bronze-red flash. The ½-inch dome was framed with a high emerald green 3/8-inch band (then electric blue from another angle). Thus, the appearance of a ‘Poached Egg’, the rather unflattering nickname that was given to ‘Flame’.

One writer described the stone thus: “Suppose you put an egg in a frying pan. Directly the egg hits the pan, the white spreads out, leaving the yolk standing in the centre. This is what the exquisite stone looks like, only the yolk is a striking blood-red, raised above and surrounded by beautiful blue-green opal.” The cut and shape are highly unusual and enhance the natural formation of the stone. Under differing lights and angles, the stone reflects numerous combinations of color in a unique and remarkable way.

A Brisbane jeweller submitted the stone to the Queensland Geological Survey. It was established that traces of ginko, a fossil plant (Chinese maiden hair fern), occurring in Jurassic rocks but not in any opal deposits, were impressed on the back of the gem. The asking price for this unusual opal has continued to climb over the years with each change of hands. In 1925, an offer of £2000 was made. In 1948, the stone was valued at £5000. In 1973, $US 32,000 was paid. In 1980, ‘Flame’ was for sale again at a million dollars! As of 1992, the stone was back home in Australia. In 2003, ‘Flame’ was put up for auction at Christie’s in New York but was passed in for an undisclosed reserve. (Estimated at US$250,000) Current photos confirm the beauty of this gem and no sign of crazing after 86 years of to-ing and fro-ing.

“Olympic Australis”

(picture and information courtesy of Altmann & Cherny)

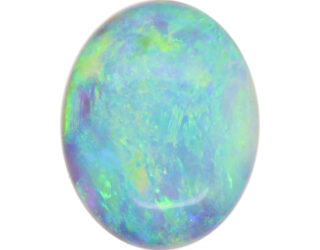

The “Olympic Australis” is reported to be the largest and most valuable gem opal ever found. It was found in 1956 at the famous “Eight Mile” opal field in Coober Pedy, South Australia. A miner working his claim found the opal at a depth of 30 feet. It was named in honor of the Olympic Games, which were being held in Melbourne at the time. This extraordinary opal consists of 99% gem opal with an even colour throughout the stone, and is one of the largest and most valuable opals ever found. The balance of 1% is the remaining soil still adhering to the stone. It weighs 17,000 carats (3450 grams) and is 11 inches long (280 mm), with a height of 4¾ inches (120 mm) and a width of 4½ inches (115 mm). It was valued at AUD$2,500,000 in 2005. Due to the purity of the opal it is anticipated that upwards of 7000 carats could be cut from the piece. However owing to it’s uniqueness, the opal will remain exactly as found.

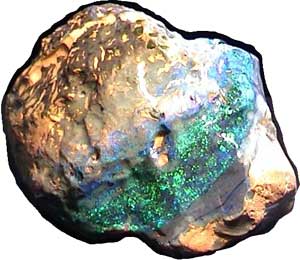

Halley’s Comet

“Halley’s Comet”, is recorded in the Guinness Book of Records as the world’s largest uncut black opal nobby. The massive stone was found by a group of opal miners on the Leaning Tree Claim at Lightning Ridge known as “The Lunatic Hill Syndicate” about the time “Halleys Comet” appeared in Australian skies.

It weighs 1982.5 carats and measures 100 x 66 x 63 mm, or 4 x 2-5/8 x 2-1/2 in. Halley’s Comet was for sale in 2006 for AUD $1.2 million. The gem has a thick gem quality green and green/orange colour bar and is the largest gem nobby to be found at Lightning Ridge to date.

“Butterfly Stone / The Red Admiral”

The Red Admiral’ or ‘Butterfly Stone’ was discovered during World War I on the ‘Phone Line’ field. Reported to be 51 carats, the stone is of extraordinary beauty, with a predominant red pattern equally visible from all angles. It wasn’t until 1920 that the stone was given the name “Butterfly” because of its resemblance to the British butterfly, the Red Admiral.

Len Cram says of this stone, “If you turn this magnificent gem on its side it changes from a butterfly to a full-length picture of a Spanish dancer in traditional broad ruffled dress, perfect in pose and movement, aflame with fiery lights.”

It passed through a number of hands, including Percy Marks and a Queensland grazier, before being purchased by the late Mrs Drysdale of Sydney. As of 2004, it was back in the care of Percy Marks & Co.

Other Stones

Other fine named gem opals from Lightning Ridge include Red Flamingo (1914), Queen of Alexander (1918), Harlequin Flame (1919), Grawin Queen (1926), Sunset Queen (1928), Light of the World (1928), Pandora (1928), Queen of Australia (1931), and Rainbow Stone (1933).

Shrouded in mystery, the ‘Hope Opal’ rests in obscurity compared to its famous collection cousin, the Hope Diamond. Also called the ‘Aztec Sun God Opal’, the 35 carat transparent blue gem with play-of-colour, features a carved human face surrounded by sun rays. Assumed to be Mexican when catalogued in 1839, the opal’s origin remains unknown.

September 2003 saw the discovery of ‘The Virgin Rainbow’ (pictured above), a 63.3mm Black Crystal Opal Belemnite Fossil in a ‘pipe’ shape, featuring gem quality colour, weighing in at 72.65 carats. The specimen was discovered at Three Mile Fields in Coober Pedy, in South Australia by Johnny Dunstan.

Sources:

The Black Opal Advocate

“Australian Precious Opal”, Andrew Cody, 1991.

Lapidary Journal

“Thank you so much. We received our necklace today and it is just gorgeous. And appreciate you getting it to us so quickly and in time for our deadline. ” (12/02/21)

“Thank you so much. We received our necklace today and it is just gorgeous. And appreciate you getting it to us so quickly and in time for our deadline. ” (12/02/21)