A new era for opal nomenclature

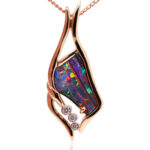

Anthony Smallwood FGAA, GG

Chairman, G.A.A. Opal Nomenclature Sub-committee

Abstract

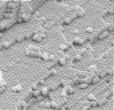

Opal is a relatively common mineral species that is found in many locations world wide. For many years a reason for the spectacular phenomenon known as play-of-colour, as seen in precious opal, remained a well hidden secret. It was not until the 1960s that Australian scientists working at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) used a new instrument now known as the electron microscope to reveal the inner structure of opal and how this is responsible for generating the play of colour of precious opal.

Opal often was referred to as a ‘semi-precious gemstone’, until unique Australian black opal was discovered and successfully marketed. Today, all varieties of precious opal, which are mined in the Australian states of New South Wales, South Australia and Queensland, support a $A500 million per year industry.

One problem that the opal industry has been required to face, however, is how does one describe a gemstone that occurs both with and without a play-of-colour, in almost every colour of the rainbow, in every tone of lightness and darkness from black to white, and in every degree of transparency from opaque to perfectly transparent. Also this unique gemstone displays differences in mineralogy that reflect the varying geological environments in which it forms.

The opal nomenclature that follows is a result of three years of striving within Australia’s opal industry to achieve co-operation and to formulate a nomenclature for opal which is accepted uniformly throughout the industry.

Introduction

For many years the terminology and nomenclature used to describe opal has been widely discussed and debated by gemmologists and those members of the gem and jewellery industry who have an interest in this gemstone. Aspects of this long-running discussion can be seen in the long list of papers published throughout the forty year history of The Australian Gemmologist. But, how to best describe opal (arguably the most beautiful of gemstones) has been a contentious and difficult issue for a very long time — and may well remain so for some time to come. However, as a consequence of factors such as: growing international and local awareness of opal as a major Australian resource; the emergence world-wide of a real desire to standardise all terminology related to gemstones; and the ever growing number of synthetics and imitations that are appearing in world markets; it has became necessary to agree on some well based concepts of how a unique gem material, such as opal, should be described. It was late in 1993 that the Australian Gemstone Industry Council requested the then President of The Gemmological Association of Australia (GAA), Grahame Brown, to initiate investigations into the possibility of establishing a uniformly accepted nomenclature for opal. After a short time, a working sub-committee of the GAA was formed that consisted of representatives of The Gemmological Association of Australia, the Australian Gem Industry Association (AGIA), and the Lightning Ridge Miners Association (LRMA). Now, after three years of discussion, correspondence, and a plethora of drafted documents, and what seemed to be a never ending train of ideas and criticisms, a final draft nomenclature has been agreed-to, ratified, published, and is presented in this paper.

The Australian Gemstone Industry Council (AGIC) has accepted this nomenclature in its final draft, as has the GAA’s 1996 and 1997 Federal Conferences in Tasmania and Perth — albeit with one or two small amendments to the final draft. Now the AGIC hopes to actively progress production of a full colour publication and video on this opal nomenclature for distribution on a world-wide basis over the next twelve months. As Chairman of the GAA’s Opal Nomenclature sub-committee I would like to express my gratitude to Jack Townsend (South Australia), Kathy Endor (Queensland) and Andrew Cody (Victoria) for their untiring efforts and fruitful discussions. Also, this author wishes to express his appreciation for the work and constant liaison of the AGIA sub-committee members Glenn McKean, Drago Panich, Peter Sherman, and Peter Evans, as well as the generous support and hospitality offered by members of the LRMA — in particular Joe Schellnegger, Maxine O’Brien, and Frank Palmer.

I would encourage all members of the GAA to read and to use this nomenclature — in their every day activities, such as buying and selling, and in scientific correspondence and lectures. This nomenclature remains, according to GAA Past President Ronnie Bauer and the AGIA’s Andrew Cody, a ‘living document’. As time passes there will be, no doubt, more discussion and criticism of this nomenclature.This will be most welcome, as are any questions — all of which may be forwarded in writing to the GAA’s Opal Nomenclature Sub-committee either care of the Federal Office of the GAA at P.O. Box A791, Sydney South NSW 1235, or direct to the author at P.O. Box 692, Sutherland NSW 2232.

The nomenclature and classification of opal, that follows, is reproduced, verbatim, from the Resolutions of the Federal Council of the Gemmological Association of Australia (dated 17th May, 1997).

Opal Nomenclature and Classification

Introduction

Opal is Australia’s National Gemstone. Australia produces 95% of the world’s natural precious opal supply. This nomenclature encompasses all types and varieties of opal to provide a standardisation of terminology but does not establish any valuation methodology.

The Australian Gemstone Industry Council Inc., in collaboration with the Australian Gem Industry Association Ltd., the Gemmological Association of Australia Ltd., the Lightning Ridge Miners Association Ltd. And the Jewellers Association of Australia Ltd., has produced the following nomenclature for the classification of opal.

Opal Classification

Opal is a gemstone consisting of hydrated amorphous silica with the chemical formula SiO2.nH2O. There are two basic forms of opal described by visual appearance.

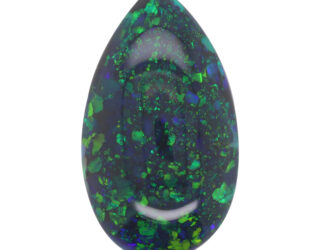

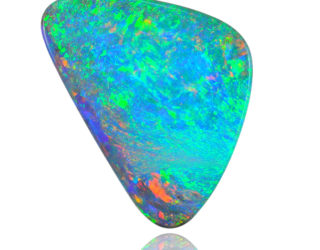

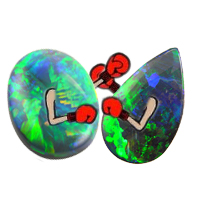

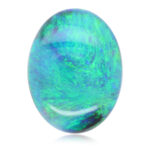

Precious Opal – is opal which exhibits the phenomenon known as play-of-colour, produced by the diffraction of white light through a micro-structure of orderly arrayed silica spheres to produce changing spectral hues.

Common Opal and Potch – is opal which does not exhibit a play-of-colour. The distinction between common opal and potch is based on formation and structure. Potch is structurally similar to precious opal but has a disorderly arrangement of silica spheres. Common opal shows some degree of micro crystallinity.

Types of Natural Opal

Natural opal is opal which has not been treated or enhanced in any way other than by cutting and polishing. There are three types of natural opal, with varieties described by the two characteristics of body tone and transparency.

Natural Opal Type 1 – is opal presented in one piece in its natural state apart from cutting or polishing and is of substantially homogenous chemical composition.

Natural Opal Type 2 – is opal presented in one piece where the opal is naturally attached to the host rock in which it was formed and the host rock is of a different chemical composition. This opal is commonly known as boulder opal.

Natural Opal Type 3 – is opal presented in one piece where the opal is intimately diffused as infillings of pores or holes or between grains of the host rock in which it was formed. This opal is commonly known as matrix opal.

Varieties of Natural Opal

The variety of natural opal is determined by the two characteristics of body tone and transparency.

Body Tone

The body tone of an opal is different to the play-of-colour displayed in precious opal. There are three varieties of natural opal based on body tone. Body tone refers to the relative darkness or lightness of the opal when ignoring the play-of-colour.

Black Opal – is the family of opal which shows a play-of-colour within or on a black body tone by reference to the AGIA Body Tone Chart N1, N2, N3 and N4 when viewed face up.

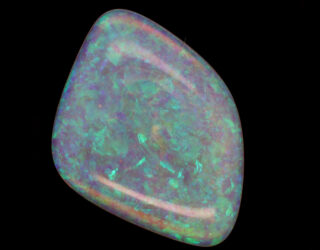

Dark Opal – is the family of opal which shows a play-of-colour within or on a dark body tone by reference to the AGIA Body Tone Chart N5, N6 when viewed face up.

Light Opal – is the family of opal which shows a play-of-colour within or on a light body tone by reference to the AGIA Body Tone chart N7, N8 or N9 when viewed face up. The N9 category is referred to as white opal.

Opal with a distinct coloured body (such as yellow, orange, red or brown) should be classified as black, dark or light opal by reference to the AGIA Body Tone Chart with a notation stating its colour hue.

Australian opal body tone chart indicator

Transparency

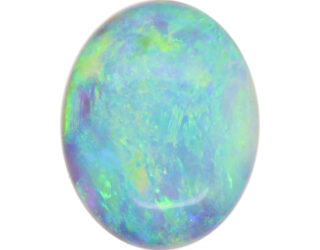

Opal shows all forms of diaphaneity and ranges from transparent to opaque. Natural precious opal which is transparent to semi-transparent is known as crystal opal. Crystal opal can have either a black, dark or light body colour tone. The term “crystal” in this context refers to appearance not a crystalline structure.

Opal Treatments

Opal can be subjected to various types of treatment. Present CIBJO guidelines state that any method of treatment other than standard cutting and polishing must be disclosed and the process used specified on all invoices, advertising and commercial documents. Types of treatments include colour enhancement, heating, painting, dying, resins and waxes, oiling or any application of chemicals. Opal is treated to change its natural appearance, structure or durability. Opal is colour enhanced in opal inlay jewellery where usually a thin solid crystal opal has black paint or glue applied or set above black painted jewellery.

Composite Natural Opal

Composite natural opal consists of natural opal laminates, manually cemented or attached to another material. The opal component is natural opal. There are three main forms of composite opal:

Doublet Opals – are a composition of two pieces where a slice of natural opal is cemented to a dark base material.

Triplet Opals – are a composition of three pieces where a thin slice of natural opal is cemented to a dark base material and a transparent top layer, usually of quartz or glass.

Mosaic and Chip Opals – are a composition of small flat or irregularly shaped pieces of natural opal cemented as a mosaic tile on a dark base material or encompassed in a resin.

Synthetic Opal

Synthetic Opal is material which has essentially the same chemical composition and physical structure as natural opal but has been made by laboratory or industrial process. Synthetic composites exist as synthetic doublets, triplets or mosaics and must be disclosed as synthetic composites.

Imitation Opal

Imitation Opal is material which imitates the play-of-colour of natural opal, but does not have the same physical and chemical structure or gemmological constants as natural opal.

Classification Reports

Classification reports for the following types of opal should include these details:

Natural Opal

-

Type of opal

-

Variety of opal as Black opal, Dark opal or Light opal with a body classification from N1 (Black) to N9 (White) based on the AGIA Body Tone Chart.

-

Transparency as opaque, translucent or transparent. Note if it is crystal opal.

-

Weight and dimensions

Treated Opal

-

Type of opal

-

Variety of opal as Black, Dark or Light opal

-

Transparency as opaque, translucent or transparent. Note if it is crystal opal.

-

Type of Treatment and process if known

-

Weight and dimensions

Composite Opal

-

Type of composite as doublet, triplet, mosaic or chip opal

-

Treatment process, where relevant

-

Dimensions

Synthetic and Imitation

-

Gemmological category including manufacturer (if known)

-

Description (Body Tone)

-

If composite, mention type as doublet, triplet, mosaic or chip

-

Weight and dimensions, only dimensions if composite

Origin

Any indication of the origin of opal by the use of geographical location should not be used unless it is qualified as an indication of the type of locality only as recommended by the International Confederation of Jewellery, Silverware, Diamonds, Pearls and Stones (CIBJO) such as Lightning Ridge type black opal.

How to Use the New Opal Nomenclature

This nomenclature for opal has been designed for use throughout the gemstone and jewellery industry, not only in Australia but internationally. While preparing this nomenclature, the sub-committee has been cognisant of conventions of international trade organisations, such as the International Confederation of Jewellery, Silverware, diamonds, pearls and stones (CIBJO), the International Colored Gemstone Association (ICA), as well as the linguistic problems associated with different languages and the differing connotations these languages may place on an internationally acceptable nomenclature.

This new nomenclature has not been designed to force any changes to the various colloquial terms used to describe opal in Australia, or indeed in countries overseas such as Mexico. Colourful language, Australian colloquial terms for opal, and terms that have been a part of the Australian scene for hundreds of years have added significantly to the mystique and folklore of everyday language used on the opal mining fields. Expressive local terms and older historical terms always will exist in the opal miner’s vocabulary. These will remain to have their rightful place in our gemstone history and in the tale-telling for years to come.

The purpose of the nomenclature, therefore, remains to provide a basic description of the gemstone we all prize and know as opal. This nomenclature is for everyone to use and understand. Simple descriptive terms, that can be used by the majority of people, from the customer to the scientist, have been chosen. These provide the gemstone industry as a whole with a logical and unbiased way of grading and evaluating opal. However, simple terms do become difficult when the many different types, formations, pseudomorphic fossil replacements, mineralogical types, and geological occurrences of Australian opal are considered.

Having said that, there are a few items of terminology which it is hoped this nomenclature will remove from common usage. In particular, the terms that have been deliberately removed, due to the linguistic problems they create, are ‘semi-black’, ‘grey’, and ‘solid’.

To begin with the first part of the nomenclature, mention is made of precious opal, potch and common opal. The best way of determining the difference between these is to observe whether or not the opal you are viewing shows the phenomenon which we all know as play-of-colour. It is possession of this optical phenomenon for which opal is most prized. The differentiation between these basic forms of opal is therefore quite simple. If the opal displays a play-of-colour it is termed precious opal. If a play-of-colour is not displayed, then the opal is either common or potch opal. While it is recognised that the term precious is neither a scientific nor gemmological term, it is retained in this nomenclature for simplicity, and with the intention of further enhancing the value of opal as a gemstone by removing it from any historical association with ‘semi-precious’ gemstones.

In an attempt at keeping the nomenclature simple to use, the terms common opal and potch opal have not been separated. It must be recognised, however, that there are distinct mineralogical differences between potch and common opal. (Jones & Segnit, 1971).

The term ‘solid’ has been removed from opal terminology, for the simple reason that all types of opal are essentially solid from a scientific point of view. That is, opal does not exist naturally either as a liquid or a gas. ‘Solid’ has been replaced by the gemmological term natural opal. Correlating with this use is the recommendation that when describing doublets and triplets that the term composite be used instead of ‘assembled’. This also is the terminology currently recommended by CIBJO.

Essentially there are three types or forms of natural opal, which are termed simply opal, boulder opal and matrix opal. Perhaps the most contentious issue in the nomenclature concerned introduction of the term body tone, to describe the comparative lightness or darkness of an opal as distinct from its play-of-colour. Technically, it would have been best just to have two types of ‘body tone’ — either ‘black or white’ or just ‘light or dark’. However, the sub-committee rightly decided not to attempt to change too much of the terminology that had been in common use for over a hundred years. So, inclusion of the term black opal was considered to be an imperative. Following much discussion the term body tone was included in the nomenclature to describe the comparative lightness or darkness of opal — irrespective of its play-of-colour. The term tone, which is used by colour science, is in agreement with terminology used internationally to describe the lightness or darkness of particular hues or colours.

The Scale of Body Tone ranges from N1 to N9. The prefix “N” reflects the neutral tone of this scale.The steps in the scale of body tone, which are arranged to indicate approximately equal decreases of darkness, are difficult to reproduce accurately on the printed page. A rough gauge can be obtained by printing this scale with the assistance of a good computer and a quality laser or ink jet printer.

After examining current industry standards, the N4 category was decided to be the cut-off point for black opal. The AGIA is currently attempting to produce a scale of body tone, using commercially available computer scanning devices and suitable software. However, at the time of publishing this paper, this scale is not yet available. The current reference, used by the Lightning Ridge Miners Association, is the neutral tone scale specified in the American Geological Society’s Rock-colour chart † . This has proved to be a good guide, for in most instances it will be possible to correlate the different ‘tone scales’ into a simple and repeatable system. An acceptable descriptive term was sought also to describe those opals that have distinct body colours or hues, such as those displayed by both Mexican fire opal and honey opal from Lightning Ridge — considerable amounts of which consists of common or potch opal. However, as an acceptable all round term could not be found to describe these opals, the committee decided to describe them by determining their body tone/s, their primary and secondary body colour/s or hues, and their transparency.

To determine the body tone of an opal, then, one examines the piece of opal, face-up, and determines (by visual comparison) its position in the scale of body tone.

-

If the tone of the opal appears darker than N4, then the opal may be classified a black opal. Consequently, any opal with a body tone darker than N4, irrespective of hue, can correctly be termed black opal. Some boulder opal possesses this body tone, so it is very correctly termed black boulder opal. It is also appreciated that some very dark red Mexican-type opals would have dark enough body tones to be categorised as black opal.

-

If the opal is lighter than N4, and its tone corresponds to N5 or N6 on the scale of body tone, then it is classified as dark opal. If, in addition, this opal has a decided hue colour, it is additionally classified as, for example, a dark blue opal.

-

If, on the other hand, the tone of the opal corresponds to N7, or lighter, it is classified as light opal. If this light opal also has a hue, then it is termed, for example, a light yellow opal.

When to term an opal a crystal opal also provided considerable discussion. The key to classification as crystal opal is really the transparency of the opal. Perhaps a better term would have been ‘transparent opal’; but any change in terminology from crystal to ‘transparent’ may take many many years to progress. The obvious problem with the term crystal opal is, of course, the basic fact that that opal has no crystal structure. Again the sub-committee decided that it was unwise to change a term that had been in common use for so many years. The sub-committee further believes that overseas gemmological communities may yet force a change in this usage, if strict terminology is ever to be implemented.

The range of transparency considered acceptable for defining crystal opal (transparent to semi-transparent) was taken straight from Robert Webster’s discussion on transparency in his world-renowned textbook Gems. The committee decided that transparency did not need to be re-defined in the nomenclature; but just stated as a classifying category.

To grade the transparency of an opal with the nomenclature, how transparent the opal is must be determined. If the opal is only translucent, then it is not termed crystal opal. It should be remembered that in some instances the play-of-colour of crystal opal will be so strong or brilliant that assessment of transparency, by the normal ‘read-through’ criterion, may not be possible as the opal can not be ‘read-through’. When this occurs the best test of transparency would be to ‘look-through’ the opal with transmitted light. If transparency exists then this will be readily apparent. If the material remains only translucent, then it is correctly labelled as light opal. It is hoped that future scientific advances may yield a better and more accurate method of assessing transparency.

A note also should be made concerning the removal of the term ‘jelly’ opal. The basic facts are that due to the extreme transparency of this opal it becomes a type of lower quality crystal opal that displays subdued low quality play-of-colour. In spite of any restriction applied by this terminology the term ‘jelly’ opal will probably remain in colloquial use for many years to come.

The description of composite stones requires only a small change in nomenclature. Instead of these opals being described as ‘opal doublets’ or ‘opal triplets’, the nomenclature emphasises their composite nature by terming these doublet opals and triplet opal s. In this terminology, which emphasises the composite nature of these opals, it is the first word of the term that precisely identifies the material.

The rest of the nomenclature discusses opal treatments, synthetics and imitations. These are not associated with the descriptive nomenclature for natural opals, but have been included to complete the nomenclature. These descriptions are in accordance with the latest edition of CIBJO’s Classification of materials and Rules of application for diamonds, gemstones, and pearls.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank Peter Sherman and Frank Palmer for providing specimens for examination. Rudy Weber’s photographic talents are gratefully acknowledged.

Sources :

-

Australian Opal & Gem Industry Association

-

Australian Gemmologist (publication)

“Thank you so much. We received our necklace today and it is just gorgeous. And appreciate you getting it to us so quickly and in time for our deadline. ” (12/02/21)

“Thank you so much. We received our necklace today and it is just gorgeous. And appreciate you getting it to us so quickly and in time for our deadline. ” (12/02/21)